The Effect of Government Type on COVID-19 Restrictions

Originally published in Towards Data Science

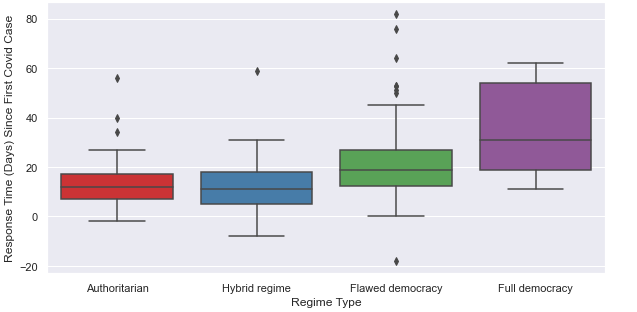

At first glance, it seems that authoritarian governments had much quicker initial responses to COVID-19 than did democratic governments. But is this a correct statement? (Image by author)

It’s been over a year since the first outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic. Since then, we have seen countries dealing with the pandemic in vastly different ways, and many people have pondered the indicators that could be used to predict countries’ varying responses and experiences. Some scholarship suggests that democratic governments (rather than authoritarian governments, such as China’s) are the key to a successful response for controlling the pandemic, due to democracy’s accountability to the people (Alon et al., 2020). Research from the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace offers a more critical view, arguing that even democratic countries such as South Korea and Italy employed methods bordering on authoritarianism, such as privacy-invasive digital contract tracing apps or criminal penalties for breaking quarantine (Kleinfeld, 2020).

In this article, I examine the relationship between government response to COVID-19 and country’s level of democracy. I ask whether the regime type of a government, as described by the Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU), has an impact on that government’s response. I hypothesize that authoritarian countries respond quicker to enact restrictions on internal movement, and that democratic countries respond slower. This article is meant to introduce exploratory analyses investigating the first few months of the COVID-19 pandemic in relation to government type and encourages future research.

I use Python and standard data science packages for my analyses. I use BeautifulSoup to scrape the Democracy Index from Wikipedia. I use pandas to conduct most of my data wrangling, slicing, merging, and manipulation. I use seaborn for plotting. The Jupyter Notebook used to conduct these analyses is available on my GitHub.

Data

I use data from two sources:

- OxCOVID19 Database: This is Oxford University’s compiled database of COVID-19 data. It is an extensive collection of several databases that include not just standard epidemiological statistics related to COVID cases and deaths, but also data about mobility patterns, weather patterns, and government response indicators. I use the

EPIDEMIOLOGYtable to determine the first COVID-19 case by country. I also use theGOVERNMENT_RESPONSEtable, which includes information on containment and closure policies taken by governments in response to the pandemic (this is part of the Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker (Mahdi et al., 2020)). I recommend you to check out the whole list of indicators, which can be found in the codebook. In this post, I focus specifically on one of the indicators:c7_restrictions_on_internal_movement - Democracy Index: The Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) calculates a numeric score to measure democracy for each country, with higher values corresponding with more democratic governments. This democracy score is mapped to one of four regime types: Full Democracy, Flawed Democracy, Hybrid, and Authoritarian. The Democracy Index is gathered from its corresponding Wikipedia page.

A little about the Democracy Index

EIU’s 2020 Democracy Index is used to measure democracy and regime type (The Economist Intelligence Unit, 2020). The Democracy Index ingests 60 different indicators for each country to calculate a numeric score representing democracy, with higher values corresponding with more democratic governments. This democracy score is mapped to one of four regime types: Full Democracy, Flawed Democracy, Hybrid, and Authoritarian. The Democracy Index is scraped from its Wikipedia page. While the Democracy Index has its own criticisms and limitations (which will be discussed later in the article), several studies, including that of Bashar and Tsokos (2019), claim that it is the most comprehensive democracy indicator.

The date of the first COVID-19 case for each country is calculated from OxCOVID19’s epidemiology table by determining the first entry with more than 0 number of cases. The stringency of internal movements is sourced from OxCOVID19’s government response table. This specific indicator can take one of the following values: 0 (no measures), 1 (recommended not to travel between regions/cities), 2 (internal movement restrictions in place), and Blank (no data). This analysis focuses on Level 2 restrictions because it aims to connect the most stringent government measures with authoritarianism.

Results

At first glance, authoritarian countries seem to have responded faster than democratic countries in enacting strict rules about internal movements. Some authoritarian countries (such as Libya and Venezuela) enacted restrictions days before reporting their first COVID-19 case.

Figure 1 groups speed of response to enact internal restriction measures by regime type. The more authoritarian the regime type of the government, the quicker the stringent response on internal movement restrictions. This seems to confirm the hypothesis that authoritarian governments act quicker to enact internal restrictive measures, whereas democratic governments are slower to do so.

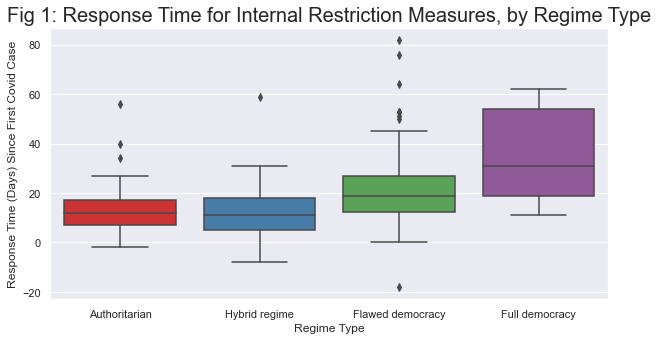

However, upon separating the speed of response by the date of the first COVID-19 case, the analysis shows that the date of first infection has a large influence on quickness of response. Figure 2 shows the government response time, separated by regime type, with the date of the first COVID-19 case aggregated by month and by week. For later dates of first COVID-19 cases, the authoritarian nature of the regime seems to have less impact on response time.

In the response times aggregated by month, the mean of the authoritarian regimes’ response times is noticeably quicker in the first two months, compared to other regime types. By the third month, the means seem to equalize across all regime types. In the response times aggregated by week, the downward trend becomes apparent as time goes on. For the countries with earlier first COVID-19 cases (before Week 8), authoritarian regimes tended to respond quicker than other regime types as indicated by the red data points. For the countries with later first COVID-19 dates (i.e. after Week 8), the regime type tended to have less of an influence in response time, as the data points are closely clustered and less variable.

Overall, the date of the first case of COVID-19 is influential upon the number of days it took for a government to enact restrictions, although the regime type of that government is not negligible. One way to interpret this can be that, for countries with earlier first cases of COVID-19, authoritarian regimes were more likely to enact stringent internal movement measures. For countries with later first cases of COVID-19, the regime type had less of an influence on stringency measures.

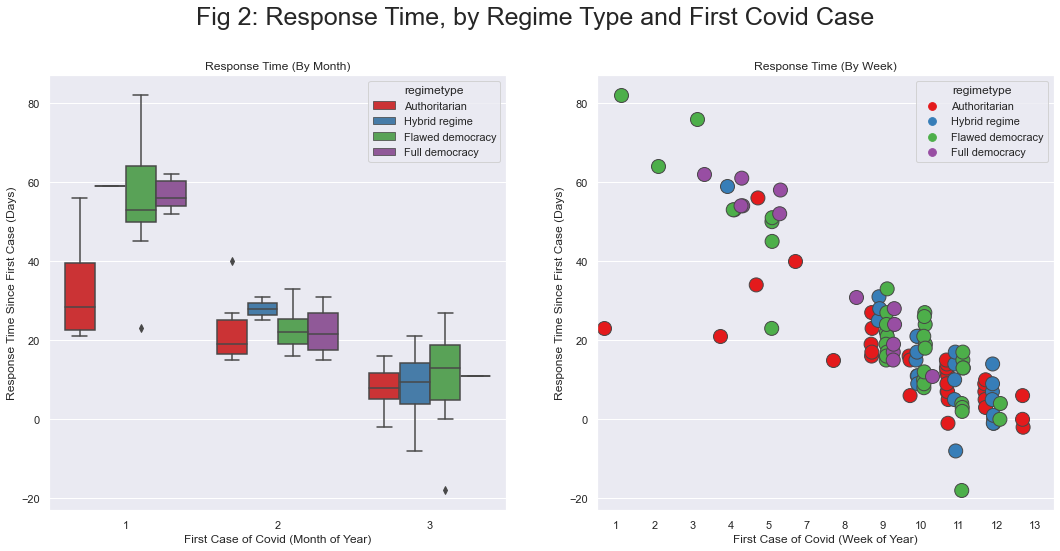

Figure 3 shows a government's response to impose internal movement restrictions for countries that experienced their first case of COVID-19 before and after February 15, 2020. February 15 was chosen as the cutoff date because, as seen in Figure 2, around Week 8 was when clustering behavior began to emerge. The eighth week of 2020 began with the date January 16.

For countries with first case before February 15, authoritarian countries responded on average around 20 days quicker. For countries with first case after February 15, all countries tended to respond quicker, with authoritarian regimes having less of an influence on response time. For countries with first case after February 15, democracies tended to take the longest to respond, while this trend is not as apparent for countries with first cases before February 15.

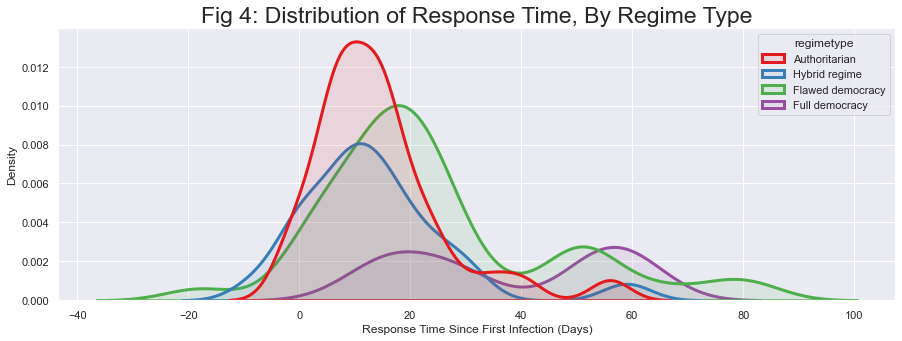

Figure 4shows the distribution of responses for each regime type. Authoritarian, hybrid, and flawed democracy regimes tend to be unimodal with long right tails, meaning that there was some unity in terms of their responses, but with some variety outside of the mode. The distribution of democratic regimes' response time, as indicated by the purple line, are less certain. The distribution of democratic regimes' response time is bimodal and variable, suggesting that the responses for different democratic regimes varied greatly.

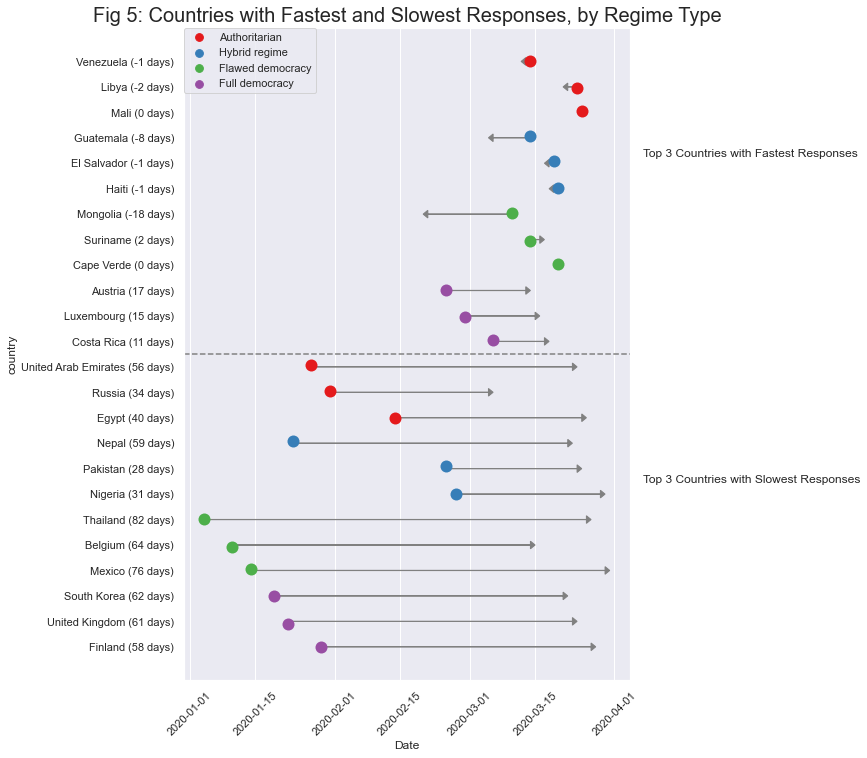

Figure 5 plots the top 3 countries with slowest and top 3 countries with fastest response, for each regime type. The dot indicates the date of the first COVID-19 case, and the end of the arrow indicates the date of the first response to enact internal movement restrictions. An arrow going to the left indicates the country having responded before their first case. Above the dotted line are the top 3 countries per regime type that responded the quickest. Below the dotted line are the top 3 countries per regime type that responded the slowest.

This graph confirms the observations made above, that countries with later first cases of COVID-19 responded quicker than countries with earlier first cases of COVID-19. However, even within this framework, we can note that the response of the quickest democratic countries is vastly different from the response of the quickest countries in the other 3 regime types. Even the fastest democratic countries did not respond proactively (i.e. before a confirmed case of COVID-19), whereas other regime types did.

As for countries with the slowest responses, there seems to be little variability among regime types. Countries with earlier first cases of COVID-19, regardless of regime type, tended to take a longer time to respond than countries with later first cases of COVID-19.

Discussion & Limitations

This project has shown that while in some cases authoritarian regimes responded faster with implementing internal restrictions, many other factors affected this observation. Nearly all regime types with later COVID-19 cases responded quickly, not just authoritarian regimes, and not all authoritarian regimes responded quickly. This aligns with the view that democratic and authoritarian governments have their own strengths and weaknesses, and neither is exclusively better at dealing with the threat of COVID-19 (Stasavage, 2020).

There are several outstanding factors not included in this analysis. Examples of factors not included in this analysis include country population, COVID-19 severity, and country history with previous pandemics. Future researchers are encouraged to investigate factors such as geographic proximity of countries to China, where the initial outbreak of the virus occurred. Perhaps one of the reasons Mongolia responded so quickly (18 days before their first COVID-19 case) was due to their sharing a border with China.

Validity of Data Sources

It is important to be critical of the data sources used in this analysis. The EIU’s Democracy Index was used as a proxy for countries’ level of authoritarianism and democracy, but there have been criticisms of the index. For example, Bashar and Tsokos (2019) suggest that the EIU’s Democracy Index may not be very accurate, as it does not take into consideration the interactions and correlations among the collected data.

There have also been some gaps in the OxCOVID19 database as well. There was no data about case numbers for the following countries: Vanuatu, Pitcairn Islands, Yemen, Falkland Islands, Solomon Islands, Hong Kong, South Sudan, Macao, Malawi, Turkmenistan, Tajikistan, and Lesotho. There may also be concerns about the accuracy of the first case of COVID-19 calculated for each country. One study uses statistical methods to show that authoritarian governments are likely to have manipulated the data they published about their COVID-19 numbers (Kapoor et al., 2020). The dates of the first COVID-19 case may be inaccurate and the analysis of this paper misleading, due to the possibility that the data in the database are inaccurate or falsified.

Future Directions

This study looked only at the time it took countries to enact severe restrictions on internal movement. Future research is encouraged to replicate this study for other kinds of restrictions in conjunction with World Values survey data. Do countries that value trade more tend to be slower enacting restrictions of international travel controls? Do countries that value education more tend to be slower in enacting restrictions on school closures? This analyses in this study can be enriched with additional data about each country, such as GDP, state of health infrastructure, and history with previous pandemics. There are many directions for extending this current study into new understandings about countries’ responses to the global pandemic.

==========

References

Alon, I., Farrell, M., & Li, S. (2020). Regime Type and COVID-19 Response. FIIB Business Review, 9, 152–160.

Bashar, R., & Tsokos, C. (2019). Statistical Classification of Democracy Index Scores of Countries of the World.

Codebook for the Oxford Covid-19 Government Response Tracker (2020). GitHub Repository. Retrieved November 18, 2020 from https://github.com/OxCGRT/covid-policy-tracker/blob/master/documentation/codebook.md.

Democracy Index. (2020). Democracy Index. Retrieved November 29, 2020, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Democracy_Index.

The Economist Intelligence Unit. (2020). Democracy Index 2020. Retrieved March 27, 2021, from https://www.eiu.com/topic/democracy-index.

Kapoor, M., Malani, A., Ravi, S., & Agrawal, A. (2020). Authoritarian Governments Appear to Manipulate COVID Data. arXiv: General Economics.

Kleinfeld, R. (2020). Do Authoritarian Or Democratic Countries Handle Pandemics Better?. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Retrieved November 29, 2020, from https://carnegieendowment.org/2020/03/31/do-authoritarian-or-democratic-countries-handle-pandemics-better-pub-81404.

Mahdi, A., Blaszczyk, P., Dlotko, P., Salvi, D., Chan, T., Harvey, J., Gurnari, D., Wu, Y., Farhat, A., Hellmer, N., Zarebski, A., Hogan, B., & Tarassenko, L. (2020). OxCOVID19 Database: a multimodal data repository for better understanding the global impact of COVID-19. medRxiv.

Stasavage, D. (2020). Democracy, Autocracy, and Emergency Threats: Lessons for COVID-19 From the Last Thousand Years. International Organization, 1–17. doi:10.1017/S0020818320000338.